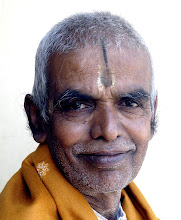

Mathihalli . Madan Mohan,Senior Journalist and Columnist

No,1 Journalists Colony, HUBLI 580032

Tel No 2374872 ; Mobile : 94480 74872

Panchayat Raj System – Karnataka Experience

It is more than a quarter century ever since Karnataka pioneered democratic decentralisation experiment in Karnataka, providing a paradigm shift in the approach to the rural development from the centralized governance to the participatory one.

Much water has flown under the bridge since then. Taking cue from Karnataka, the then Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi took initiative to get the 73rd and 74th Constitutional amendments passed to provide place and protection for the panchayat raj institutions in the Constitution with a view to freeing these institutions from the whims and fancies of the state governments. Karnataka was the quick to fashion a new panchayat law in the context of the Constitutional amendment in 1993, went in for a comprehensive amendment a decade later on in 2003 designed to provide more powers and financial sinews to enable the panchayat raj institutions to discharge their new responsibilities.

Right from 1987, (barring two years of inaction), the three tier panchayat raj system is being managed by the representatives elected in five elections held so far and as of today, over 95,000 elected representatives (with around 91,000 belonging to gram panchayats alone) are in charge of the zilla, taluk and gram panchayats in the thirty districts of Karnataka . They have the task of handling Rs. 11,000 crores plan and nonplan budget (of which non plan accounts for a lion share to mainly to meet the salary component of the state government employees seconded for services in the PRIs). In the process, the gram panchayat, at the lowest tier, which is the cutting edge of the new experiment, gets on an average anywhere between Rs. 80 to 100 lakhs of plan funds per years, which by any standards a princely sum compared to the pittance they received in the earlier dispensation. Besides, Karnataka has introduced a panchayat window in its budget from the year 2005-2006 giving details of the funds assigned to three tier system in the areas assigned to them under the Constitution.

Though twentyfive years are a too small a period for making any meaningful evaluation of the path breaking experiment designed to bring a new administrative ethos, the prognosis is far from satisfactory. As George Mathew, the renowned social scientist has put it; the panchayat raj system in Karnataka has slid from a pristine position to an apology for democratic decentralisation.

For, the centralisation reigns supreme even as the panchayat system continues to totter in an atmosphere marked with distrust, jealousy and what not. The concept of the primacy of the zilla parishat in the development matters has been given a gobye and centralized control of the deputy commission over the affairs in the district as before has been brought back. The system has not been able to develop its own roots and endear itself to the rural community for the service of which it has been established. In a way it appears to be the Cindrella of Karnataka, a beautiful princess not wanted by anybody.

The question is what has gone wrong with the experiment with all the inputs it has received so far? The problem in retrospect appears to be more of attitudinal change than law. There is a marked reluctance on the part of the concerned in the system to come to terms with the ethos of the transfer of power that the experiment presages.

The panchayat system has been squarely caught in swirl of problems at three levels- namely the political, administrative and internal contradiction.

At the political level, the fact of the matter is hat the political leadership, which has put the system in place initially, has become wary of it. As many as eight governments including the present one administered singly or severally by the three major political parties have ruled Karnataka ever since decentralisation experiment made its debut way back in 1987 by the Ramakrishna Hegde government. . None of them at any time have evinced a genuine interest in carrying the experiment further. . As succinctly put by Mani Shankar Iyer, the Congress ideologue on decentralisation and former Union Minister for Panchayat raj, “every time the government change, the panchayat raj in Karnataka comes under threat. Karnataka’s approach according to him has been “two steps forward and one step backward” phenomenon.

The slide back had started initially during the regime of Hegde itself especially after the untimely demise of Abdul Nazir Sab, the coauthor of the move, which got accentuated in the subsequent days.

For example, the provision relating to creation of panchayat raj development parishat, which is something analogous to the national development council which would serve as a clearing house for policies on the panchayat raj, remains on paper.

Apart from anything, this has deprived the PRIs of the only link with the government as a result of which they feel that they have become orphans. The move to have a District Planning Committees for planning integrated development of the rural and urban areas in the district has never been given a trial. The evolution of a new planning process starting from villages to state level remains on paper. Besides the governments of the day at no stage have shown interest in implementing the recommendations of the state finance commission, which are constituted to work out the devolution of funds between the state and the urban and rural local self governments. As a matter of fact the recommendations of the Third State Finance Commission have been waiting to be implemented for the past three years.

On the other hand, in the name of social engineering, the government has reduced the tenure of the adhyakshas for sixty months (five years) to twenty months. This has cut at the very root of the experiment, which was to throw up the alternate new leadership in the rural areas, since none of the incumbents get time to settle themselves to run the show. And rotation system of reservation of seats at every election has proved to be disincentive for the members to perform well. For he or she is not sure whether the constituency can be retained the next time because of the rotation of reservation. . The requests made for the restoration of the five year term and put two tenure limit for the reservation of seats, have fallen on deaf ears. Once the government even moved to withdraw the powers given to the gram panchayats through an amendment. But was rebuffed by the Governor who returned the bill on the grounds that it was violative of the Constitution.

The disinterest of the political leadership in the experiment had its impact on the attitude of the legislators, who have perceived the system, as something of a threat to the hegemony they have been enjoying all these days. It is no longer a secret that the first law of the panchayat raj was passed during the Hegde regime, even as the legislators cutting across the party barriers had their own reservations in decentralisation and transfer of powers to the panchayat raj institutions (PRIs). Hegde had to make compromise in the form providing exofficio membership of the panchayat bodies to get the bill passed.

Their main worry all along has been that the PRI members would emerge as alternate centres of power in the districts and taluks to threaten their own position. For example, a Minister apprehends that a successful zilla panchayat president could be his potential rival and like wise the MLAs feel that a successful taluk panchayat president could be so in the taluks. The present day MLAs thoroughly relish the power to sanction schools, roads and buildings, allotment of houses and house sites and drinking water schemes, and the power to get teachers transferred. If these are taken away and given to PRIs, they would become irrelevant. Therefore they have been losing no opportunity to deride and denigrate panchayat institutions. Hardly any meaningful discussions take place in the assembly. It is the same plight in the Legislative Council, where onethird of the members represent the local bodies, where the bulk of the voters comprise of PRI members.

At the administrative level, the problem is a bit different. Their interest or otherwise in the system has a direct bearing on the thinking of the political masters. When the political masters wanted it way back in the middle of eighties, the IAS brigade burnt midnight oil to prepare blue print for the successful implementation of the experiment. But when the political masters showed signs of disinterest, the bureaucracy could not be expected to the different. But even in this atmosphere too, some of the good things which have taken place, have happened because of the few good intentioned officers. For example, the government was dragging its feet on implementation of the law passed in 2003 giving more powers to the PRIs. It was at the higher level of bureaucracy that a few well intentioned officials led by the then Additional Chief Secretary and Development Commissioner Mr. Chiranjivi Singh who put together the act together in the middle of 2004, prodded by the question raised by the Assurance Committee chairman Mr. D R Patil Congress MLA.. The accountability and transparency that the system envisages has been something of an anathema to the middle level bureaucracy.

The PRI members have contributed in their own way to the conundrum through internal bickerings. The members of the three tiers are more worried about the powers they have and do not have between themselves rather than put their heads together to make a success of the responsibilities given tot hem under the law to provide an administration responsive to the peoples needs and solves problem with their collaboration. Several of the NGOs including the Gram Panchayat Hakkottaya Sammelana, have been trying to mobile the support for the revitalization of the system and a state level convention was held at Udipi in the second week of December to discuss several issues. But all these would be of no use in the absence of a professed commitment at the political level. At the moment there are no signs of the same happening in Karnataka.

(eom) 16th Dec. 2011 .

.

No comments:

Post a Comment